Tennessine: Element Properties And Uses

Description

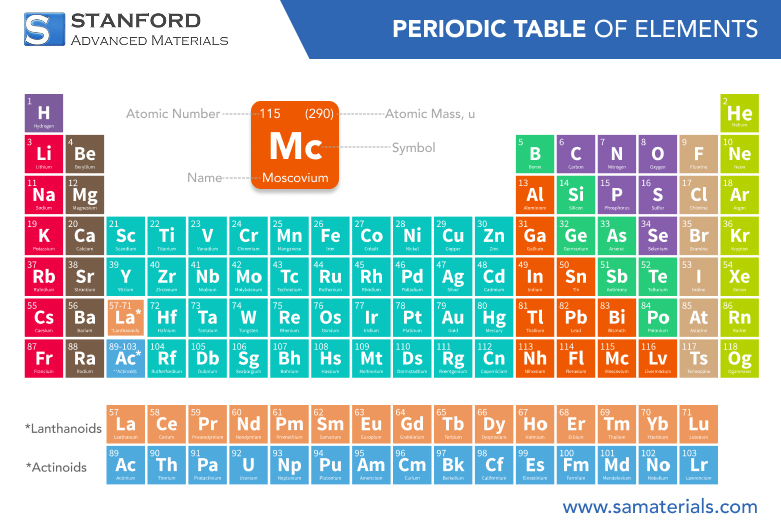

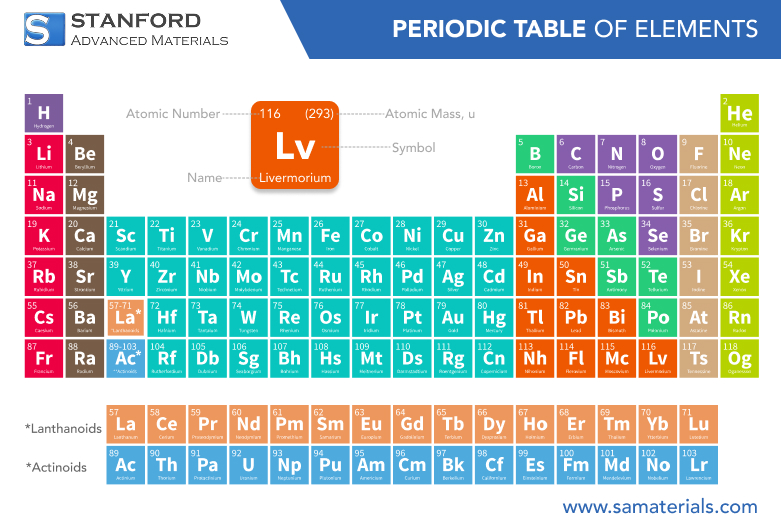

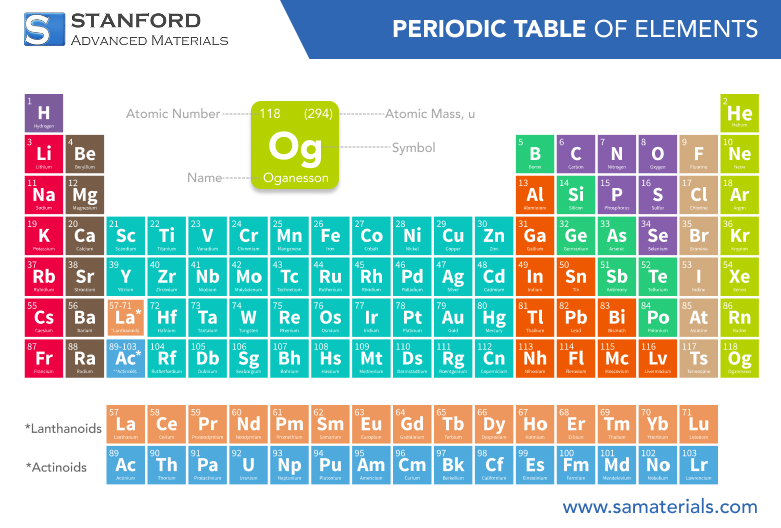

Tennessine (Ts) is a synthetic, superheavy, and highly radioactive element with the atomic number 117. One of the newest additions to the periodic table, it occupies a foundational position in modern nuclear research. Tennessine exists for moments in fractions of a second before decaying into lighter elements, but its creation marks a breakthrough in the modern search for superheavy nuclei.

History and Naming

Tennessine was first synthesised in 2010 through a joint effort by Russian and American scientists from the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee, USA. The experiment targeted berkelium-249 (²⁴⁹Bk) with ions of calcium-48 (⁴⁸Ca) to produce Tennessine-294 atoms.

The new atoms broke down almost instantly, but their characteristic alpha-particle emissions provided evidence of the existence of element 117.

In 2016, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) officially recognised the discovery and approved the name "Tennessine", after the United States state of Tennessee, to honour ORNL, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Tennessee's contributions to the research and discovery of superheavy elements.

Atomic and Physical Properties

|

Property |

Value (Predicted or Observed) |

|

Atomic Number |

117 |

|

Symbol |

Ts |

|

Group / Period |

17 / 7 |

|

Element Category |

Halogen (Predicted) |

|

Density (Predicted) |

~7.2 g/cm³ |

|

Melting Point (Estimated) |

~350–500°C |

|

Boiling Point (Estimated) |

~610–780°C |

|

Most Stable Isotope |

Ts-294 |

|

Half-Life |

~20 milliseconds |

Tennessine is expected to behave as a metallic or semi-metallic halogen, unlike lighter analogues such as chlorine or iodine. Theoretical models suggest relativistic effects—due to the high velocity of inner electrons—may bestow weaker non-metallic character and perhaps metallic bonding tendencies upon it.

Chemical Properties Description

As a result of its extremely short half-life and small output of production, no actual chemical experiment has ever been performed on Tennessine. Computational chemistry and periodic trends, however, provide insight into its likely behaviour:

•Group Similarity: Tennessine is in Group 17 (the halogens) and should display some reactivity resemblance with astatine (At), the largest naturally occurring halogen.

•Oxidation States: Calculated oxidation states are –1, +1, and +3, of which +1 and +3 must be more stable due to relativistic stabilisation effects.

•Chemical Reactivity: It is expected to form simple compounds such as Tennessine chloride (TsCl) and Tennessine fluoride (TsF), but none of these have been experimentally established.

Production and Synthesis

Synthesis of Tennessine involves particle accelerators, radioactive targets, and sophisticated ion-beam technology.

The synthesis includes the following key steps:

1. Target preparation: A thin layer of berkelium-249, prepared at the High Flux Isotope Reactor at ORNL, is deposited on a foil of titanium.

2. Ion bombardment: A calcium-48 beam is accelerated to high energy and bombarded onto the berkelium target.

3. Nuclear Fusion: Sometimes the collision of nuclei results in the formation of a superheavy compound nucleus (Tennessine), which releases neutrons and decays almost immediately.

4. Detection: Carefully designed detectors measure the alpha decay chain to confirm the presence of the new element.

Due to its low yield—only a few atoms per experiment—and rapid decay, each observation demands high precision and international cooperation.

Applications and Scientific Significance

Tennessine's short half-life and minute production eliminate any industrial or commercial uses, but its scientific impact is significant:

•Nuclear Structure Studies: The study of Tennessine enables physicists to observe proton and neutron behaviour in the superheavy region of the periodic table.

•Theoretical Confirmation: Its discovery confirms nuclear shell model predictions and the quest for the "island of stability", a theoretical region where superheavy elements may have longer half-lives.

•Technological Development: Equipment and methods developed to produce Tennessine—such as advanced target preparation, particle beam manipulation, and detector technology—have influenced advancements in nuclear medicine, materials science, and accelerator physics. For more information, please check Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Tennessine?

Tennessine (Ts) is a synthetic, radioactive element with atomic number 117, produced by high-energy nuclear fusion reactions of berkelium and calcium isotopes.

Why is it named Tennessine?

The element is named after the U.S. state of Tennessee in acknowledgment of the significant role played by its research institutions in the discovery.

How is Tennessine made?

It is produced by bombarding targets of berkelium-249 with calcium-48 ions in a particle accelerator, yielding only a few atoms at a time.

What are its chemical properties?

It is expected to behave as a heavy halogen, possibly exhibiting metallic characteristics, with oxidation states of –1, +1, and +3.

Does Tennessine possess any useful industrial applications?

No practical applications exist as of now due to its instability, but its synthesis advances technology in nuclear science and high-precision instrumentation.

What is the advantage of studying Tennessine?

It increases understanding of superheavy element stability, nuclear forces, and relativistic effects on chemical behaviour.

Bars

Bars

Beads & Spheres

Beads & Spheres

Bolts & Nuts

Bolts & Nuts

Crucibles

Crucibles

Discs

Discs

Fibers & Fabrics

Fibers & Fabrics

Films

Films

Flake

Flake

Foams

Foams

Foil

Foil

Granules

Granules

Honeycombs

Honeycombs

Ink

Ink

Laminate

Laminate

Lumps

Lumps

Meshes

Meshes

Metallised Film

Metallised Film

Plate

Plate

Powders

Powders

Rod

Rod

Sheets

Sheets

Single Crystals

Single Crystals

Sputtering Target

Sputtering Target

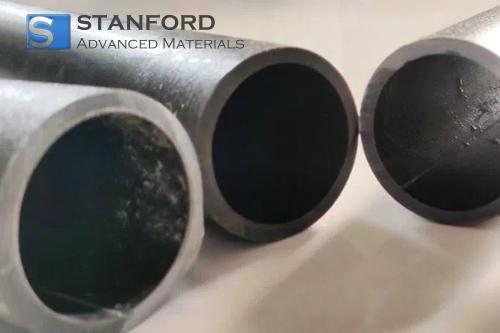

Tubes

Tubes

Washer

Washer

Wires

Wires

Converters & Calculators

Converters & Calculators

Write for Us

Write for Us

Chin Trento

Chin Trento