Creep In Metallurgy And Alloys

Understanding Creep

In metallurgy, creep is a fundamental process of deformation and is defined as the time-dependent, irreversible strain, which develops in material under a constant load, usually above 0.3 to 0.5 times its melting point, Tm. Unlike instantaneous plastic deformation, creep occurs over a relatively slow period of time and is therefore one of the principal degradation processes in metal parts and alloys used for high temperatures in steam power plants, aerospace engines, and automotive components.

Creep deformation normally occurs in three stages:

1. Primary creep - the rate of creep decreases with increasing time due to strain hardening.

2. Secondary (steady-state) creep - constant creep rate; most important for design.

3. Tertiary creep - accelerated damage leading to rupture.

Understanding these stages is of paramount importance in predicting material life and avoiding catastrophic failures in high-temperature components.

Factors Affecting Creep in Alloys

Temperature

The dominating factor is the temperature factor. An increase in temperature increases atomic mobility, and an increased diffusion rate increases creep strain. For instance, when the temperature increases from 600°C to 700°C, austenitic stainless steels exhibit a tenfold increase in their creep rate.

Stress

The creep rate often rises as a power-law function of applied stress, ε̇ = Aσⁿ, where n is different for each alloy. For high-temperature superalloys, for example, n may be 4–7, while pure metals normally exhibit n ≈ 1–3.

Material Composition

Elements such as Mo, W, Ti, Al, Cr, and Nb enhance alloy phases or form stable precipitates, giving improved creep resistance.

Microstructure

Finer, more stable precipitates, larger grains, and chemical control of the grain boundary region all act to lower creep deformation. The dominant mechanism of creep in fine-grained materials is grain boundary sliding, while in coarse-grained materials the dominant mechanism is dislocation creep.

Applications and Implications of Creep Resistance

Aerospace Engineering

Turbo machinery blades in jet engines operate at 1000–1100°C, which is about the melting point of nickel-based superalloys. By using creep-resistant materials, dimensional stability is maintained and catastrophic engine failure is avoided.

Power Generation

Superheater and reheater tubes in coal and nuclear plants likewise operate continuously in the 550–650°C range and require steels that possess very high resistance to creep rupture.

Automotive Systems

Alloy requirements for exhaust valves, turbocharger rotors, and high-performance engine parts require retention of strength up to 700–900°C.

Methods of Enhancing Creep Resistance-Specific

1. Alloying

Alloying additions change phase stability and impede dislocation motion.

Case Example: Ni-based Superalloy IN738

Contains 8.5% Co, 16% Cr, 3.4% Al, 3.4% Ti, 1.7% Mo, 2.6% W

• Creep rupture life at 870°C, 150 MPa:

> 1 000 hours

This performance stems from the high fraction (~70%) of the precipitates γ′ (Ni₃Al/Ti) resisting dislocation creep.

2. Heat Treatment

Heat treatment can control precipitate size and distribution.

Case Example: Ti-6Al-4V alloy

• Solution treatment + ageing decreases creep rate at 500°C by 30–40%

• Reason: Refining α + β lamellar structures to prevent grain boundary sliding.

3. Grain Boundary Engineering

Increasing grain size reduces the grain boundary sliding, which is one of the major mechanisms of creep at high temperature.

Case Example: Austenitic Stainless Steel 316H

• Large-grain variant exhibits 2–3× longer creep life compared to the fine-grained form at 600°C, 100MPa

• Grain size increased from ASTM 8 to ASTM 4.

4. Surface Treatments

Coatings protect the material against oxidation and degradation by environmental influences.

Case Example: MCrAlY Coatings (M = Ni, Co) on Turbine Blades

• Improve resistance to oxidation above 1100°C

• Enhance the creep life of the underlying alloy by 10–15%, since surface degradation has been retarded.

Creep Behaviour of Some Common Alloys

|

Alloy Type |

Common Applications |

Creep Resistance Characteristics |

|

Jet engine components, power plant turbines |

High creep resistance at elevated temperatures due to solid solution strengthening and precipitation hardening |

|

|

Stainless Steels |

Automotive exhaust systems, industrial machinery |

Moderate creep resistance enhanced by alloying elements like chromium and molybdenum |

|

Titanium Alloys |

Aerospace structures, high-performance engines |

Good creep resistance with low density, suitable for high-stress environments |

|

Gas turbines, aerospace engines |

Exceptional creep resistance through complex microstructures and stable phase formations |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is creep in metallurgy?

Creep is defined as the slow and permanent deformation in any material under load, especially at high temperatures, for a long period.

Why is creep resistance important in alloys?

The creep resistance ensures that the component retains mechanical integrity under continuous thermal and mechanical stresses.

Which industries most benefit from creep-resistant materials?

These include aerospace, energy industries (nuclear/thermal), automotive, metallurgy, and chemical processing.

How can the creep resistance of an alloy be improved?

Through alloying, heat treatment, grain boundary control and protective surface coatings.

Are there alloys specifically engineered for high creep resistance? Certainly, nickel-based single-crystal superalloys of CMSX-4, René N5, and titanium alloys of Ti-6242 are optimised for creep resistance under extreme environmental conditions.

Bars

Bars

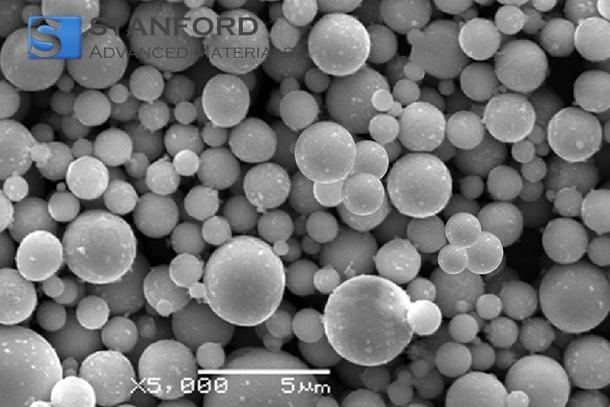

Beads & Spheres

Beads & Spheres

Bolts & Nuts

Bolts & Nuts

Crucibles

Crucibles

Discs

Discs

Fibers & Fabrics

Fibers & Fabrics

Films

Films

Flake

Flake

Foams

Foams

Foil

Foil

Granules

Granules

Honeycombs

Honeycombs

Ink

Ink

Laminate

Laminate

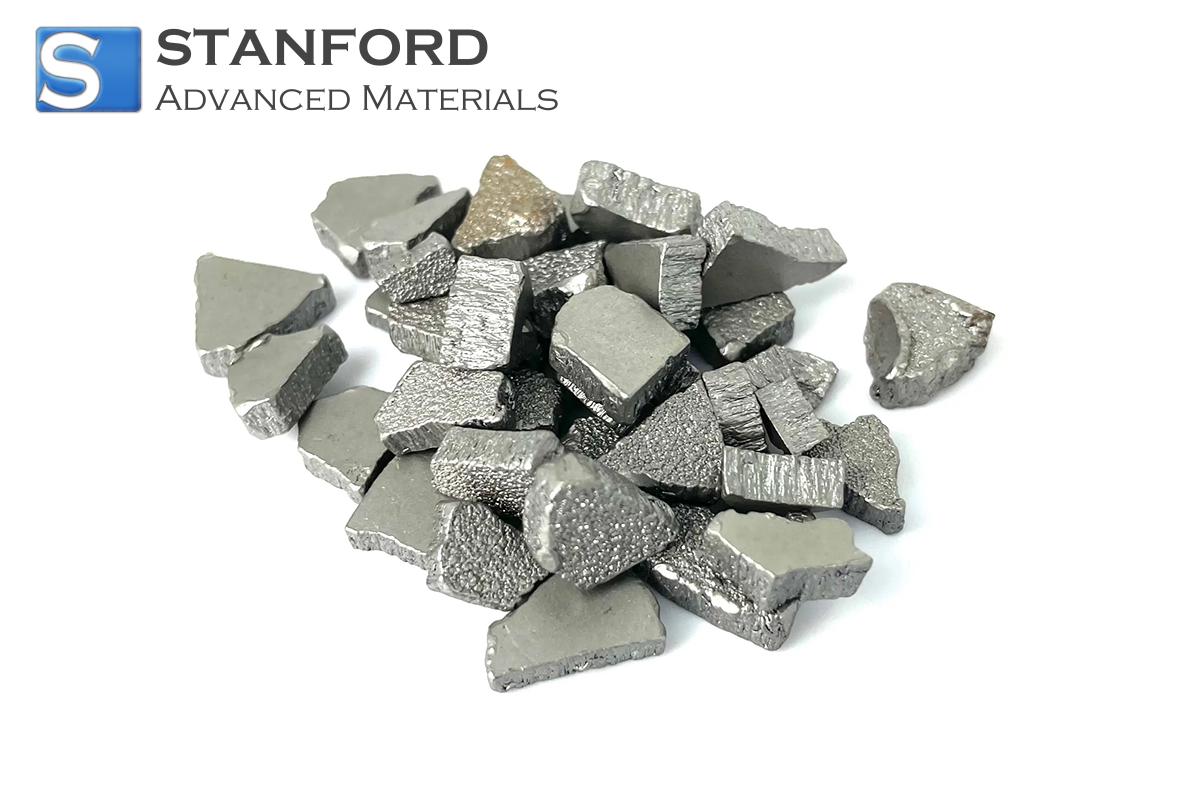

Lumps

Lumps

Meshes

Meshes

Metallised Film

Metallised Film

Plate

Plate

Powders

Powders

Rod

Rod

Sheets

Sheets

Single Crystals

Single Crystals

Sputtering Target

Sputtering Target

Tubes

Tubes

Washer

Washer

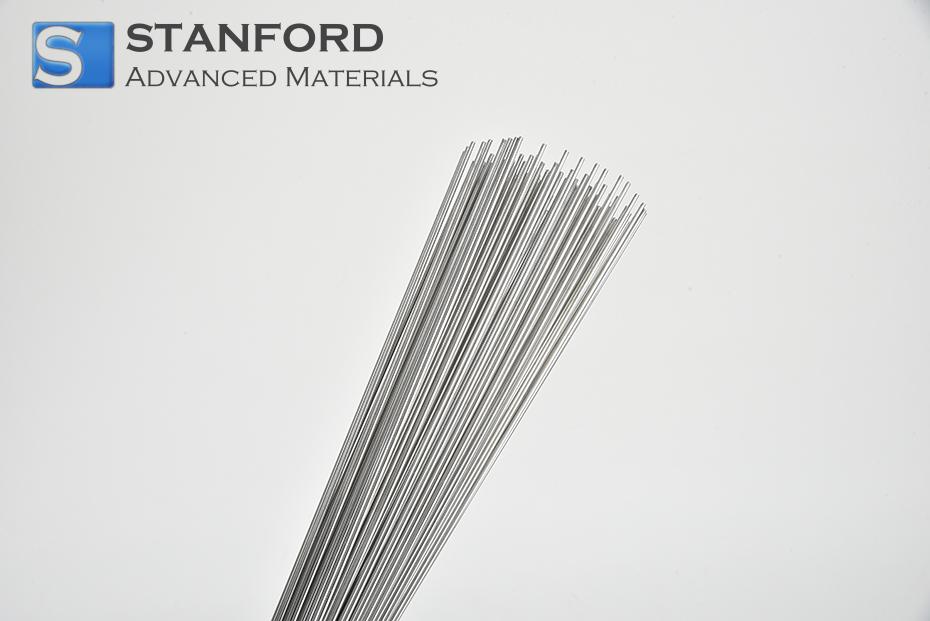

Wires

Wires

Converters & Calculators

Converters & Calculators

Write for Us

Write for Us

Chin Trento

Chin Trento