Spin Hall Effect: Mechanism And Applications

The SHE describes the generation of a spin current in the absence of external magnetic fields due to transport of electrons in materials, representing an important advance in the field of spintronics and opening doors for the development of next-generation electronic devices.

Mechanism of the Spin Hall Effect

The Spin Hall Effect arises as a consequence of the interaction of the electron's charge with its spin; this is an intrinsic property of some materials due to spin-orbit coupling. This effect occurs when an electric current flows through a non-magnetic conductor, causing the electrons to experience a deflection due to spin-orbit interactions.

In simple terms, as the current passes through the material, the electrons with spin-up orientations are deflected in one direction, while the spin-down electrons are pushed in the opposite direction. This separation of electron spins results in the accumulation of opposite spins on opposite sides of the conductor, creating a transverse spin current. Notably, this effect occurs without the need for an external magnetic field, in contrast to the traditional Hall effect, which requires one.

The Spin Hall Effect is understood herein as a voltage created across the material by the accumulation of spin-polarised electrons with their spin axes oriented perpendicular to the current direction. In this connection, such an effect is essential in various spintronic devices that manipulate electron spins, in addition to charge, in an attempt to enhance performance and efficiency in general electronic systems.

Key Factors Controlling the Spin Hall Effect

Several reasons affect the efficiency of the Spin Hall Effect in a material, including material composition, temperature, and layer thickness. These parameters are crucial in optimising SHE for practical applications.

1. Material Composition:

The strength of the spin-orbit interaction in a given host material is perhaps the most critical aspect that defines the magnitude of the SHE. The heavy metals such as platinum and tungsten, among others, and certain topological insulators are known to exhibit strong spin-orbit coupling, hence showcasing an enhanced SHE. These materials are particularly effective in generating spin currents, making them appropriate candidates for applications pertaining to spintronics.

For example, platinum has a high spin Hall angle, which denotes the efficiency with which charge currents are transformed into spin currents.

2. Temperature:

Temperature plays an influential role in the efficiency of the Spin Hall Effect. The efficiency of the generation of a spin current increases at lower temperatures because the phonon scattering—scattering of electrons due to interaction with the vibrating atomic lattice—tends to decrease. That is, in fact, the reason why the majority of the newly designed spintronic devices operate at cryogenic temperatures in order to enhance the performance of the SHE.

3. Thickness of the layer:

The thickness of the conducting layer also plays an important role in the generation of a spin current within the material. The thicker the layer is, the higher the possible probability of spin scattering, which can reduce the effective spin diffusion length and hence the generated spin current. Therefore, careful control over layer thickness is necessary to optimise the performance of SHE-based devices.

Applications of the Spin Hall Effect

Such a unique ability of the spin current to be generated and manipulated without an external magnetic field makes the Spin Hall Effect highly valuable in a wide range of innovative technologies. Among the most pronounced applications are the following:

1. Spintronic Devices:

Spintronics exploits the spin of the electrons in addition to their charge for information processing. The SHE allows for the realisation of spin-based transistors and memory devices operating with much higher speed and lower power consumption compared to conventional charge-based electronics. In contrast to conventional transistors that operate by managing the flow of charge, spintronic devices utilise electron spin as an additional degree of freedom for storing and processing information.

Example: The Spin Hall Effect has been used to develop a spin-based transistor that provides real prospects for faster and energy-efficient devices. Such transistors are likely to find application in computationally intense applications, including next-generation high-performance computing and memory systems.

2. Magnetic Memory:

The Spin Hall Effect plays a vital role in the development of magnetic random access memory, which is a non-volatile type of memory. SHE enables the manipulation of magnetic domains inside the memory cells, contributing to better MRAM performance by allowing faster switching times and the possibility for higher data storage densities.

Example: MRAM devices exploiting the Spin Hall Effect are capable of data storage with lower power consumption and higher efficiency than conventional memory devices and, therefore, are very suitable for applications in mobile devices and computers and any other kind of digital storage.

3. Quantum Computing:

In quantum computing, qubit stability and manipulation are crucial for reliable operation. The Spin Hall Effect allows for generation and control of spin currents, contributing to qubit stabilisation and control. These spin currents help increase the coherence times of qubits, of pivotal importance for improving the fidelity and operational performance of quantum computers.

Example: The Spin Hall Effect is currently under investigation as a way to improve the control of topological qubits, a promising kind of qubit that is more robust against noise and decoherence.

Spin Hall Effect Parameters

A number of key parameters can quantify the effectiveness of the Spin Hall Effect in a given material. These parameters help researchers and engineers understand the efficiency of spin current generation and guide the design of devices relying on SHE.

|

Parameter |

Description |

Typical Values |

|

Spin Hall Angle |

Efficiency of charge to spin current conversion |

0.1 - 0.2 |

|

Resistivity |

Electrical resistivity of the material |

10 - 100 μΩ·cm |

|

Spin Diffusion Length |

Distance over which spin current persists |

1 - 10 nm |

|

Critical Current Density |

Current density required for spin current generation |

10^6 - 10^8 A/m² |

|

Temperature Range |

Operational temperature range for SHE devices |

4 K - 300 K |

For more information, please check Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM).

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the Spin Hall Effect?

The spin Hall effect is a physical effect consisting of the creation of a perpendicular spin current, thanks to the spin-orbit interaction of the material, which induces the separation of electron spins.

2. In what ways is the Spin Hall Effect different from the conventional Hall Effect?

Unlike the conventional Hall effect, which involves an external magnetic field to generate a voltage perpendicular to an electric current, in the Spin Hall Effect, the generation of spin currents does not need an external magnetic field but relies merely on intrinsic spin-orbit interactions.

3. What kind of materials are best suited for observing the Spin Hall Effect?

The materials with strong spin-orbit coupling, like platinum, tungsten, or specific topological insulators, are ideal for observing the Spin Hall Effect. Such materials exhibit pronounced spin-orbit interactions that lead to efficient generation of spin current.

4. What are the main applications of the Spin Hall Effect?

While the Spin Hall Effect is currently mainly used in spintronic devices and magnetic memory technologies such as MRAM, it is under investigation for quantum computing applications aimed at improving qubit coherence and, correspondingly, operational fidelity.

5. What are the key challenges that must be overcome in order to realise a wide range of Spin Hall Effect-based devices?

Some of the key challenges are in identifying and synthesising materials with optimal properties of spin-orbit coupling, scalable manufacturing processes of the devices, and the integration of spintronic components with the existing electronic system efficiently.

Bars

Bars

Beads & Spheres

Beads & Spheres

Bolts & Nuts

Bolts & Nuts

Crucibles

Crucibles

Discs

Discs

Fibers & Fabrics

Fibers & Fabrics

Films

Films

Flake

Flake

Foams

Foams

Foil

Foil

Granules

Granules

Honeycombs

Honeycombs

Ink

Ink

Laminate

Laminate

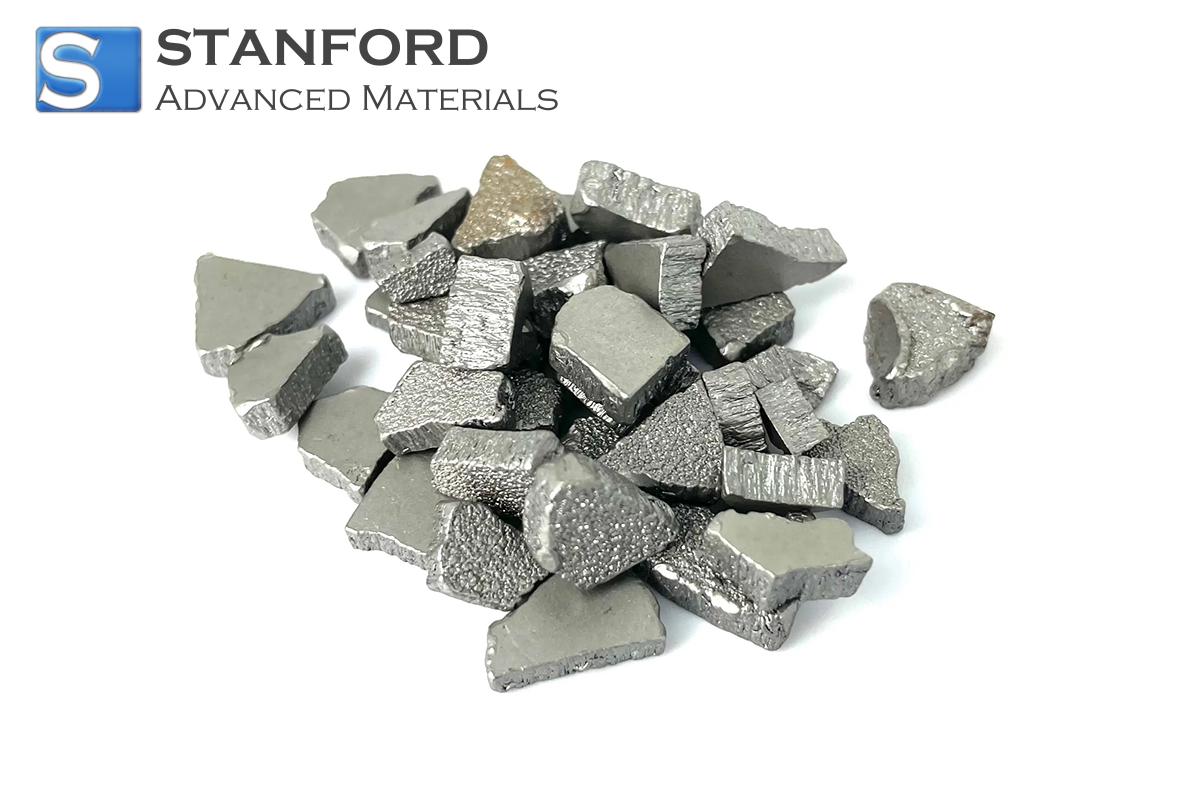

Lumps

Lumps

Meshes

Meshes

Metallised Film

Metallised Film

Plate

Plate

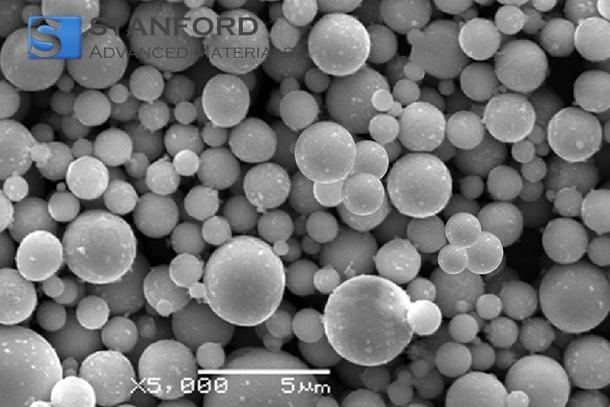

Powders

Powders

Rod

Rod

Sheets

Sheets

Single Crystals

Single Crystals

Sputtering Target

Sputtering Target

Tubes

Tubes

Washer

Washer

Wires

Wires

Converters & Calculators

Converters & Calculators

Write for Us

Write for Us

Chin Trento

Chin Trento