Precious Metal Catalysts: The Performance Amplifier - The Support

Chapter 1: Introduction

A precious metal catalyst is a material that can alter the rate of a chemical reaction without being consumed in the final products. While nearly all precious metals can serve as catalysts, the most commonly used are platinum, palladium, rhodium, silver, and ruthenium, with platinum and rhodium having the widest applications. Their partially filled d-electron orbitals readily adsorb reactants on the surface with moderate binding strength, facilitating the formation of intermediate "active compounds" and thereby granting high catalytic activity. Coupled with superior properties such as high-temperature, oxidation, and corrosion resistance, they have become crucial catalytic materials.

Precious metal catalysts are essential in numerous key fields due to their exceptional catalytic activity and selectivity. In environmental remediation, they are extensively used in automotive exhaust purification systems and industrial combustion processes to efficiently convert toxic pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds into harmless gases, significantly reducing emissions. They also play vital roles in other areas of environmental protection, such as air purification and wastewater treatment. In industrial production, they are central to chemical synthesis, enhancing reaction rates and product selectivity through catalysed reactions such as hydrogenation, oxidation, and carbonylation. Furthermore, in the energy sector, precious metal catalysts are integral to hydrogen energy technologies, essential for hydrogen production, fuel cell operation, and hydrogen storage, thereby advancing the conversion and utilisation of clean energy.

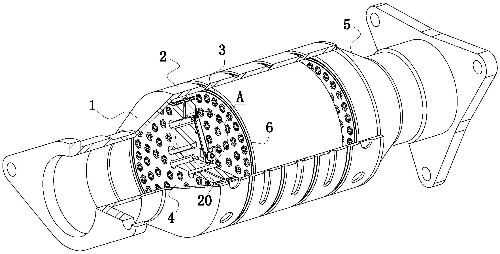

Fig. 1 Automotive Three-Way Catalytic Converter Structural Diagram

However, the inherent drawbacks of precious metals—their global scarcity, high cost, and susceptibility to deactivation via sintering, leaching, and poisoning—severely constrain their large-scale commercial application. The key to addressing these challenges lies not in the precious metals themselves, but in their "foundation"—the support. Modern catalytic science reveals that the support is far from an inert physical scaffold; it is a multifunctional platform and crucial partner for overcoming the limitations of precious metals. Its core value is manifested in two key aspects:

The support, with its high specific surface area and abundant surface defects, provides secure "anchoring sites" for precious metal nanoparticles or even single atoms, enabling atomic-level dispersion. This not only maximises the exposure of active sites, significantly improving atomic utilisation efficiency, but also effectively prevents the migration and agglomeration (sintering) of particles at high temperatures through physical spatial constraints and strong interactions, fundamentally enhancing catalyst stability.

Profound interactions exist between the support and the precious metal. Through electronic effects (e.g., Strong Metal-Support Interactions, SMSI), the support can modulate the electron cloud density of the precious metal, optimising its adsorption strength for reactants, thereby enhancing intrinsic catalytic activity and selectivity. Additionally, the inherent surface acidity/basicity or redox properties of the support can catalyse reactions synergistically with the precious metal active sites, enabling complex reaction pathways unattainable by single components, collectively building efficient bifunctional catalytic systems.

Chapter 2: Core Functions and Mechanisms of the Support

In the design of precious metal catalysts, the support is not merely a passive vessel, but a key component that plays multiple active roles. Its functional mechanisms profoundly influence the final performance of the catalyst, primarily evident in four areas:

1. Dispersion and Stabilisation

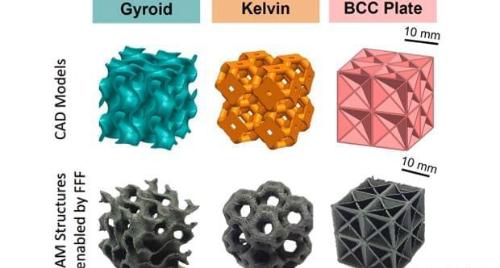

The primary function of the support is to act as an "anchorage" for precious metal nanoparticles. A high specific surface area (e.g., hundreds of m2/g) provides numerous loading sites, allowing the precious metal to be highly dispersed at the nanoscale or even atomic level, thus maximising the exposure of active sites and improving atomic utilisation efficiency. Without support, precious metal nanoparticles, due to their high surface energy, readily migrate, agglomerate, and sinter at elevated temperatures, resulting in a drastic reduction in active surface area and deactivation. Furthermore, the pore structures of many supports can create a confinement effect, restricting metal particles within nanocavities or interlayers—creating "nano-reactors"—which physically hinders their movement and growth, further enhancing thermal stability.

Fig. 2 Porous Materials

2. Electronic Effects

Profound electronic interactions exist between the support and the precious metal, most notably the Strong Metal-Support Interaction (SMSI). Using the Pt/TiO2 system as an example, after high-temperature reduction treatment, some Ti4+ on the TiO2 surface is reduced and migrates to cover the Pt nanoparticle surface, forming a sub-oxide overlayer. This process is accompanied by electron transfer from TiO2 to Pt, altering the electron cloud density of Pt and consequently modulating its adsorption strength and mode for reactant molecules (e.g., CO, O2). This "remote control" via electronic effects can significantly enhance the catalytic activity and selectivity for specific reactions and even confer resistance to poisoning.

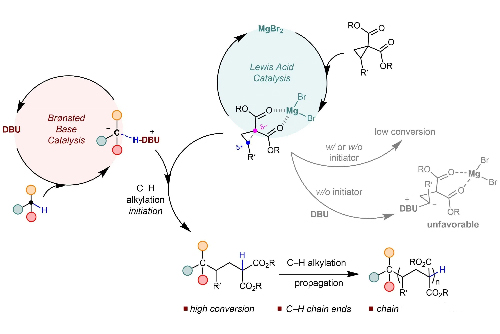

3. Synergistic Catalysis

Many supports are not inert; their surfaces possess acidic/basic sites or inherent catalytically active sites, enabling catalytic cooperation with the precious metal, constituting a "bifunctional" mechanism. For instance, in catalytic reforming in petroleum refining, Pt in the Pt/γ-Al2O3 catalyst is responsible for the hydrogenation/dehydrogenation of olefins, while the acidic sites on the γ-Al2O3 surface facilitate the isomerisation of carbocations; the two functions work together to reconstruct hydrocarbon molecules. Another example is in fuel cell anode reactions, where RuOH species in PtRu/C catalysts promote water activation, providing OH species to adjacent Pt sites to oxidise CO, alleviating the issue of Pt catalyst poisoning by CO.

Fig. 3 Organic Small Molecule/Metal Cooperative Catalysis

4. Mass and Heat Transfer

The physical structure of the support determines the transport efficiency of reactants and products. Precise tuning of the porous structure (including pore size, pore volume, and connectivity) optimises diffusion rates, avoiding reaction efficiency losses due to mass transfer limitations. Macropores favour rapid mass transfer, mesopores are suitable for loading nanoparticles and facilitating reactions, and micropores can enable shape selectivity. Simultaneously, excellent supports possess high thermal stability and thermal conductivity, allowing them to withstand high-temperature exothermic reaction environments, rapidly remove reaction heat, and prevent the collapse of the catalyst structure and sintering of the active component caused by local overheating.

Chapter 3: Main Types of Supports for Precious Metal Catalysts and Their Characteristics

1. Oxide Supports

Oxide supports are the most extensively studied and widely applied category.

γ-Al2O3: Known as the "workhorse support," its advantages include high specific surface area, suitable surface acidity, and good mechanical strength. These properties make it ideal for automotive three-way catalysts (loading Pt, Pd, Rh) and hydrodesulfurisation catalysts (loading Pd).

SiO2: Typically possesses a neutral surface and a high specific surface area. Its surface inertness means it does not interfere with the intrinsic activity of the precious metal. Tunable mesoporous SiO2 can be prepared via templating methods, finding widespread use in selective hydrogenation and oxidation reactions.

TiO2: Beyond its high specific surface area, its most significant feature is the ability to form strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI) with precious metals, markedly enhancing catalytic performance. Concurrently, TiO2 is an excellent photosensitive semiconductor; when combined with Au, Pt, etc., it shows substantial potential in photocatalysis for water splitting and pollutant degradation.

CeO2: Possesses unique oxygen storage capacity (OSC), allowing it to switch rapidly between oxidising and reducing atmospheres via the Ce4+/Ce3+ cycle, effectively regulating the oxygen concentration in the reaction environment. This characteristic makes it indispensable in automotive exhaust purification (as a co-catalyst) and redox-related reactions.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Oxide Support Characteristics

|

Support Type |

Specific Surface Area |

Surface Property |

Key Characteristics |

Typical Applications |

|

γ-Al2O3 |

High |

Weakly Acidic |

High mechanical strength, good thermal stability |

Auto exhaust cleanup, Hydrotreating |

|

SiO2 |

High |

Neutral |

Tunable pore size, inert surface |

Selective Hydrogenation, Oxidation |

|

TiO2 |

Medium |

Amphoteric |

SMSI, Photocatalytic activity |

Photocatalysis, CO Oxidation |

|

CeO2 |

Medium |

Basic |

Excellent Oxygen Storage Capacity |

Three-Way Catalysts, Water-Gas Shift Reaction |

2. Carbon Material Supports

Carbon materials are notable for their conductivity and structural diversity.

Activated Carbon: Features an extremely high specific surface area and abundant surface functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH), making it easy to modify and load metals. Due to its low cost, it is widely used in liquid-phase reactions (e.g., fine chemical hydrogenation) and electrocatalysis.

Carbon Nanotubes/Graphene: These novel carbon materials possess a unique sp² hybridised carbon structure, extremely high conductivity, and regular pore channels. They not only induce electronic effects with precious metals through π-π conjugation but also ensure rapid electron transfer during electrocatalysis due to their exceptional conductivity, thereby demonstrating outstanding performance in fields such as fuel cells (e.g., Pt/CNTs for oxygen reduction) and water electrolysis.

3. Zeolite Supports

Zeolites are crystalline aluminosilicates characterised primarily by their ordered microporous channel systems and tunable acidity.

Shape Selectivity: Their pore sizes at the molecular scale (typically <2 nm) allow selective passage of reactants and products based on size and shape, enabling shape-selective catalysis. For example, in Pt/zeolite-catalysed diesel hydrofinishing, straight-chain alkenes can be selectively hydrogenated while branched alkanes are retained.

Strong Acidity and Confinement Effect: Their strong acid centres, combined with the confinement of metal particles within micropores, make them excel in reactions such as alkane isomerisation and aromatization.

4. Other Novel Supports

With advancements in nanotechnology, a range of novel supports shows great potential.

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Composed of metal ions and organic linkers, they possess ultra-high specific surface area and atomically designable pore environments, making them ideal platforms for achieving single-atom dispersion of precious metals and size-selective catalysis.

Mesoporous Materials: Such as SBA-15 and MCM-41, feature highly ordered mesoporous structures and narrow pore size distributions, providing ideal channels for mass transfer and reactions of large molecules, addressing the slow mass transfer issues of microporous materials.

Carbides/Nitrides: Such as molybdenum carbide and carbon nitride, they exhibit metal-like conductivity, high chemical stability, and thermal stability. As emerging electrocatalyst supports or synergistic catalysts, they show potential to replace traditional supports.

Table 2: Comparison of Other Support Type Characteristics

|

Support Type |

Structural Feature |

Core Advantage |

Potential Applications |

|

Zeolites |

Crystalline Microporous |

Shape Selectivity, Strong Acidity |

Shape-selective Hydrogenation, Isomerisation, Molecular Sieving |

|

MOFs |

Crystalline Porous |

Ultra-high Surface Area, Designable Structure |

Single-Atom Catalysis, Gas Storage/Separation |

|

Mesoporous Materials |

Ordered Mesopores |

Uniform Pore Size, High Mass Transfer Efficiency |

Large Molecule Catalysis, Biosensing |

|

Carbides/Nitrides |

Interstitial Compounds |

High Conductivity, High Stability |

Electrocatalysis, Corrosion-resistant Catalysis |

Chapter 5: Challenges and Future Perspectives

Precious metal catalysts, while essential, face significant hurdles that drive ongoing research. The primary challenge remains their high cost and natural scarcity, which creates economic and supply chain vulnerabilities for large-scale applications such as automotive catalysis and bulk chemical production. This is compounded by their inherent tendency to deactivate, primarily through sintering—where nanoparticles agglomerate into larger, less active particles at elevated temperatures—and through poisoning by reaction byproducts. Furthermore, the performance of these catalysts is often limited by traditional support materials that function merely as passive scaffolds, failing to actively enhance or stabilise the precious metal. A deeper scientific challenge lies in the incomplete understanding of dynamic changes at active sites under real operating conditions and the precise structure-activity relationships, hindering rational design.

Future progress is closely linked to innovative strategies that maximise efficiency and durability. A central focus is on maximising atomic utilisation efficiency. This involves moving beyond simple nanoparticle dispersion to advanced architectures such as Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs), which can theoretically achieve 100% metal dispersion, and sophisticated core-shell or nano-frame structures that concentrate precious atoms at the surface where reactions occur. The "Atom-Extraction" strategy, for instance, demonstrates how alloy design can be used to pull precious metal atoms from the core of a nanoparticle to its surface, dramatically boosting efficiency while minimising loading.

Concurrently, the role of the support is being redefined from a passive spectator to an active, synergistic partner. The future lies in intelligent support design capable of precise electronic and geometric control. This includes engineering Strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI) to optimise electronic properties and using novel materials such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) or 2D layered double hydroxides (LDHs) that offer atomically defined environments to stabilise metal atoms. The concept of confinement effects, where metal particles are physically trapped within porous structures, is a powerful approach to prevent sintering.

The development paradigm is shifting from empirical discovery to rational design. The integration of machine learning, high-throughput computation, and advanced in-situ characterisation is accelerating the discovery of new materials and our understanding of catalytic mechanisms. Alongside optimising precious metal use, the long-term pursuit of low-PGM (Platinum Group Metals) and ultimately PGM-free catalysts, based on earth-abundant transition metals, continues to be a critical, albeit challenging, path towards sustainable catalysis. These combined efforts aim to break the traditional trade-offs between activity, stability, and cost.

Fig. 4 Future Nanotechnology

Chapter 6: Conclusion

In summary, the support plays multiple roles in precious metal catalysts that extend far beyond mere physical scaffolding. It is the cornerstone for achieving high dispersion, high stability, and high utilisation efficiency of precious metals, and is key to actively enhancing catalytic performance through electronic and catalytic effects. Confronting the core challenges of precious metal scarcity and instability, the future direction is clear: a shift from traditional empirical screening towards precise rational design. By constructing single-atom catalysts, core-shell structures, and developing novel multifunctional supports, we can "exquisitely decorate" precious metals at the atomic/nanoscale. This will ultimately enable us to dramatically reduce precious metal usage while multiplicatively enhancing catalytic performance and service life, providing the core driving force for sustainable development in the energy, environmental, and chemical industries.

For advanced precious metal catalyst solutions that meet these evolving demands, contact Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM).

Related Reading:

Utilising Catalyst Poisoning to Improve Catalyst Selectivity: The Role of Lindlar Catalysts

Understanding Catalyst Poisoning in Precious Metal Catalysts: Causes, Problems, and Solutions

Catalysis Redefined: Advantages of Palladium on Carbon

References:

[1] Bell, A. T. (2003). The Impact of Nanoscience on Heterogeneous Catalysis. Science, 299(5613), 1688–1691.

[2] Somorjai, G. A., & Li, Y. (2010). Introduction to Surface Chemistry and Catalysis. Wiley.

[3] Tauster, S. J., Fung, S. C., & Garten, R. L. (1978). Strong Metal-Support Interactions. Group 8 Noble Metals Supported on TiO2. Journal of the American Chemical Society, *100*(1), 170–175.

[4] Cargnello, M., et al. (2013). Control of Metal Nanocrystal Size Reveals Metal-Support Interface Role for Ceria Catalysts. Science, 341(6147), 771–773.

Bars

Bars

Beads & Spheres

Beads & Spheres

Bolts & Nuts

Bolts & Nuts

Crucibles

Crucibles

Discs

Discs

Fibers & Fabrics

Fibers & Fabrics

Films

Films

Flake

Flake

Foams

Foams

Foil

Foil

Granules

Granules

Honeycombs

Honeycombs

Ink

Ink

Laminate

Laminate

Lumps

Lumps

Meshes

Meshes

Metallised Film

Metallised Film

Plate

Plate

Powders

Powders

Rod

Rod

Sheets

Sheets

Single Crystals

Single Crystals

Sputtering Target

Sputtering Target

Tubes

Tubes

Washer

Washer

Wires

Wires

Converters & Calculators

Converters & Calculators

Write for Us

Write for Us

Dr. Samuel R. Matthews

Dr. Samuel R. Matthews